Temporomandibular Joint Disorders, the Cervical Spine, and Spinal Manipulation

In biomechanics, there is a rule that notes that the regions of the body that have the greatest mobility have the least stability; and reduced stability is coupled with greater injury and stress risk. Joints that have multiple planes of motion are particularly prone to increased stress and injury risk.

The jaw not only opens and closes, it can move side-to-side as well as protrude forward and retract backwards. These diverse planes of motion increase the risk for biomechanical problems.

The jaw is used in talking, chewing, swallowing, kissing, yawning, and in facial expressions. It is vulnerable to injury during trauma such as whiplash exposure, boxing, and other impact/collision-types of sports or activities. Certain types of psychometric stress can cause night grinding, stressing the jaw joint.

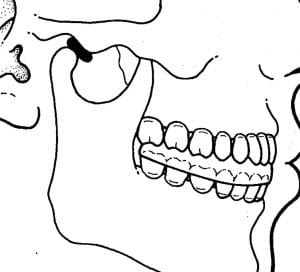

The jawbone is attached to the skull. Anatomically, the jawbone is known as the mandible. The skull is composed of many different bones that are tightly bound together. The skull bone where the mandible attaches is anatomically known as the temporal bone. The joint between the mandible and the temporal bone is the temporomandibular joint, commonly abbreviated TMJ.

Disorders of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), are referred to as the temporomandibular dysfunction, commonly abbreviated TMD.

Dental and facial experts have long understood that the function of the TMJ is inherently linked to the biomechanical function of the neck (the cervical spine). This is because of shared neurology.

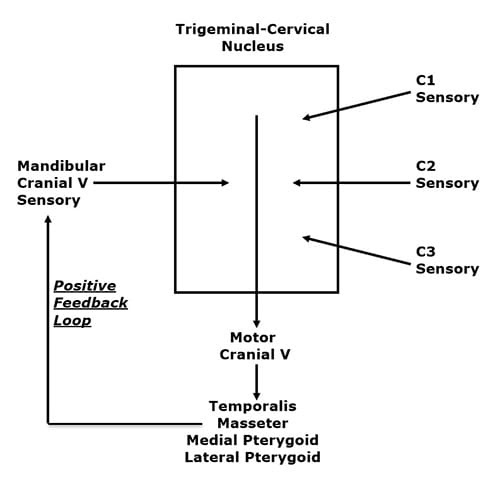

The TMJ, like all other moveable joints, has two primary categories of nerves: sensory and motor. The sensory nerves provide to the brain information such as pain, temperature, and position. The motor nerves move the joint by directing the contraction of the muscles that cross the TMJ. The motor and sensory nerves to the TMJ largely travel and exist together in the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V).

There are four muscles that cross the TMJ and control the movement of this joint. They are (also noted in the drawing above):

- Temporalis

- Masseter

- Medial Pterygoid

- Lateral Pterygoid

Please look at the drawing above. In a unique anatomical occurrence, the sensory nerve (mandibular cranial V) that innervates the TMJ, the motor nerves that move the TMJ, and the sensory nerves of the upper neck (cervicals 1-2-3), all communicate with each other in a “box,” depicted above, called the trigeminocervical nucleus. Functionally, this means that neck problems that involve the upper cervical spine nerve roots (C1, C2, C3) have the ability to influence the motor nerves that control the muscles that cross the TMJ. Again, upper neck problems can activate the four muscles that move the TMJ (temporalis, masseter, medial and lateral pterygoid muscles).

A muscular imbalance of the TMJ can cause TMJ biomechanical stress and inflammation. The consequence of this is depolarization of the sensory nerves that innervate the TMJ, causing pain and other symptoms (discussed below). This TMJ sensory disturbance sends afferent information into the trigeminocervical nucleus, creating a positive feedback loop (see above drawing), ultimately resulting in temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD).

The pertinent question for this review is:

Can biomechanical treatment, specifically chiropractic spinal manipulation, of the upper cervical spine that reduces aberrant sensory input from the upper cervical spinal nerves, be successful in the management of TMD?

A recent study was published in June 2018 in the journal Manuelle Medizin [The European Journal of Manual Medicine], titled (7):

Spinal High-Velocity Low-Amplitude Manipulation with Exercise in Women with Chronic Temporomandibular Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing to Patient Education

This study is the first prospective randomized controlled clinical trial to directly compare the effectiveness of upper cervical manipulation, sham manipulation, and education in patients with temporomandibular disorders.

The objective of this study was to investigate the effects of spinal high-velocity low-amplitude manipulation with exercise compared to patient education in patients with chronic temporomandibular disorders (TMD). Fifty-five female patients (age 18-50 years) with temporomandibular disorders were randomized to three groups:

- Cervical spinal manipulation plus neck exercise (CSM + NE)

- Sham manipulation plus neck exercise (SM + NE)

- Patient education only (PE)

Patient assessments were done at baseline, post-treatment (a minimum of 6 treatment sessions), and at a 1-month follow-up. Assessments were performed using:

- Numeric rating scale / NRS for pain intensity

- Pressure pain thresholds / PPT masseter/temporalis muscles

- Pain-free maximum mouth opening / MMO in millimeters

- Short Form 36 / SF-36 for quality of life

The cervical manipulations were applied to the upper cervical spine. The authors state:

“Cervical spinal manipulation was performed using a segment-specific technique for segmental dysfunctions of the upper cervical spine.”

The manipulation applied in this study appeared to be a sitting rotational maneuver. The physician’s middle finger was placed on the C1 transverse process. The manipulation was done posterior to anterior. Slack taken up to “exclude contraindications (such as pain or dizziness during the test) against an impulse.”

The sham spine manipulation was performed using a high-velocity low-amplitude manipulation to “give the patient the same mechanical and acoustic sensations.” It was applied to the cervico-thoracic junction by an “impulse to the spinous process of C7.”

The authors note that “temporomandibular disorders are musculoskeletal conditions characterized by painful conditions and dysfunctions in the muscles of mastication, the temporomandibular joint, and related-tissue components.”

The prevalence of temporomandibular disorders is between 3% and 15% of the population. They primarily affect middle-aged adults. Women are affected twice as often as men.

Classic TMD disorders symptoms are headache and neck pain. The authors note that because of the “neuroanatomical convergence of trigeminal and upper cervical afferents in the medullary dorsal horn of the spinal cord (trigeminal caudal nucleus),” that:

“Cervical dysfunctions can influence the temporomandibular system.”

The authors found:

“Significant differences were observed in the cervical spinal manipulation plus neck exercise group vs. the sham manipulation plus neck exercise and patient education only groups post-treatment.”

There was “significantly increased [in pressure pain thresholds] in the upper cervical manipulation group, while there were no changes in the pressure pain thresholds in both the sham manipulation and education groups.”

There were significant increases of pain-free maximum mouth opening post-treatment in the cervical spinal manipulation groups.

There were significant increases in the Short Form-36 scores post-treatment in the cervical spinal manipulation group.

There was significant improvement in the Numeric Rating Scale in the cervical spinal manipulation group.

The authors concluded:

“It is highly likely that functional integration exists between jaw and cervical movements.”

“This prospective randomized controlled trial demonstrates that in the presence of temporomandibular disorders, the high-velocity low-amplitude manipulation of the upper cervical spine combined with a neck exercise program reduced jaw pain intensity and increased the pressure pain thresholds of masseter and temporalis muscles as well as pain-free maximum mouth opening; moreover, it improved quality of life in women with temporomandibular disorders after treatment and at the 1-month follow up.”

“Our study suggests that high-velocity low-amplitude manipulation of the upper cervical spine with neck exercise can be effective for treatment of pain and dysfunction in patients with chronic temporomandibular disorders.”

“It seems reasonable to add cervical manipulation to the rehabilitation program.”

“Cervical manipulation might positively influence cervical movements, which can affect temporomandibular movements if cervical dysfunction is present.”

“Our data provide new evidence about the efficacy of treatment for temporomandibular disorders focused on the upper cervical region.”

“High-velocity low-amplitude manipulation and neck exercise was used for the management of patients with chronic temporomandibular disorders.”

“Our study proves that upper cervical spine manipulations play an important role in the treatment of pain and dysfunction in the presence of temporomandibular disorders by interruption of the nociceptive vice versa effects of trigemino-cervical convergence.”

To learn more about TMJ and how chiropractic spinal adjustment can help improve your condition, contact West Side Comprehensive Chiropractic.

REFERENCES:

1. Kaplan A, Assael L; Temporomandibular Disorders, Diagnosis and Treatment; WB Saunders Company; 1991.

2. Corum M, Basoglu C, Topaloglu M, Dıracoglu D; Aksoy C; Spinal High-Velocity Low-Amplitude Manipulation with Exercise in Women with Chronic Temporomandibular Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing to Patient Education; Manuelle Medizin [The European Journal of Manual Medicine]; June 2018; Vol. 56; No. 3; pp. 230–238.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”